May 20th, 2010 by

May 20th, 2010 by  Joern Meissner

Joern Meissner

In a market where timing is everything and prices are constantly shifting, one of the main (and obvious) priorities that executives and managers tend to miss is constant reevaluation. With aggressive competitors ready to move in on your customers, a successful company needs to be constantly aware of what is going on in their markets, what they customers want, and where their prices should be. It is not enough to simply know this information once a month or even once a week; in this technologically-reinforced fast -paced world, it is imperative that executives reevaluate their decisions constantly.

The first step in the reevaluation process to realize that you, as the executive or manager, have two valuable resources at your disposal: your employees and your computers. The second step is to trust that each can do their job.

Your computers can be set up, with even the most basic software, to run databases that can process large amount of information, from your current prices, to your prices in certain months, to your competitors’ prices. Having this information is vital, as it will tell you whether your prices are working or failing you at any given point.

A case in point here is simple: if last year’s data tells you that more people will need swimming suits in the summer and spring, push the price up in those seasons. While this may seem overly simplistic, information like this won’t make any difference if your company miss this because the information isn’t always available and isn’t accessible every day. If your competitor suddenly changes prices, you simply can’t wait three months to realize it – and another three months to change your pricing policies to try to take back some of your customers.

The second part of this process is also fairly simple: empower your employees to use these information databases to implement informed decisions. If your employee realizes that your two major competitors have suddenly dropped their prices for a similar product to yours and that you’re going to lose any chance at a profit this quarter because of it, then enable your employees to fix that problem for you. Sure, have then inform you of the problem and the solution immediately, as it happens, but in this day of instant communication with anyone, they shouldn’t have to wait every time something changes – because something will change every day.

This is the central crux of this idea: stay on top by staying informed. Put of all your skills to use by making sure that your company is running as well as it can by keeping informed and by using this constant stream of information to make important decisions on your basic pricing policies, every day.

![[Slashdot]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/slashdot.png)

![[Digg]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/digg.png)

![[Reddit]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/reddit.png)

![[del.icio.us]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/delicious.png)

![[Facebook]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/facebook.png)

![[Technorati]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/technorati.png)

![[Google]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/google.png)

![[StumbleUpon]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/stumbleupon.png)

Posted in Pricing

Tags: Aggressive Competitor, Customers, Pricing, Pricing Policy, Reevaluation

March 30th, 2010 by

March 30th, 2010 by  Joern Meissner

Joern Meissner

The iPad, Apple’s newest technological wonder, will be released on April 3rd, just a few short weeks from now, but one thing probably missing from its advertised digital bookstore, iBookstore, will be the books from the world’s sales leader in publishing, Random House.

In the Financial Times article ‘Random House fears iPad price war’, Random House chief executive Markus Dohle said that Random House was still reviewing their options, as they fear that Apple’s pricing policy is of an interest to their stakeholders. The publisher was still in discussions with their agents and authors over the decision.

Random House is a division of Bertelsmann, whose profits declined over the past year, thanks in large part to the recession. And while the company believes they will make gains this year, they are not sure that allowing Apple to control the pricing policy of their e-books is the way to go about it.

Apple’s current e-book policy is that publishers will set the price for their own books, with Apple receiving 30 cents off every dollar. While the other five major publishers (which account for nearly all of Random House’s competition) have already signed on with Apple and their iBookstore, this new pricing scheme is very different from standard publishing policies.

In standard publishing pricing, the publishers sell books to the bookstores at a wholesale rate. The bookstores then make a profit by marking up the books from the wholesale rate. Bookstores can even return unsold books. Even Amazon, one of the world’s top bestsellers and one of the darlings of e-commerce, sells its book this way. While the publishers and Apple both agree that e-books are here to stay, neither is quite sure how to actually price them successfully to make both companies and their customers happy.

In the end, Random House must realize that a price war of any type is not beneficial to their company. If Random House takes Apple’s offer of controlling their own prices, they must quickly realize that trying to price their bestsellers at a price lower than their competitors will only result in spend-thrifty customers and low revenues. And if Random House decides to take Apple’s deal and then prices their books far too low, customers will always expect that price. And they will now be simply a few touches on the touchscreen away from picking up a book from Harper-Collins or Macmillan instead.

![[Slashdot]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/slashdot.png)

![[Digg]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/digg.png)

![[Reddit]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/reddit.png)

![[del.icio.us]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/delicious.png)

![[Facebook]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/facebook.png)

![[Technorati]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/technorati.png)

![[Google]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/google.png)

![[StumbleUpon]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/stumbleupon.png)

Posted in Pricing

Tags: Apple, Apple iBookstore, Apple iPad, Customer Retention, Digital Books, Digital Pricing, E-Book Pulishing, E-book Readers, E-Books, Financial Times, Harper-Collins, iBookstore, iPad, Macmillan, Markus Dohle, Price Point, Price War, Pricing, Pricing Strategy, Publishing, Random House

March 23rd, 2010 by

March 23rd, 2010 by  Joern Meissner

Joern Meissner

Bundling is the act of grouping services and products together to create a new price point. This technique is common in most industries, but the question remains of whether the buyer or the seller actually benefits more from the bundling itself.

In the recent article ‘The Pros and Cons of Bundling’ by Anthony Tjan (The Harvard Business Review, February 26, 2010), Tjan discussed how bundling, in his opinion, ultimately benefits the seller. His argument is based on the lack of transparency in bundling; the sellers can group products and services together in a way that hides how much the customer pays for each individual item. This illusion then prompts the customer to pay more for simple items than they would if the bundle had been broken into a product-by-product invoice.

An illustration of this idea is when customers buy all-inclusion cruise packages – the customer does not know how much they are paying for each individual part of the cruise but only the total price. For example, the overall price for one person could $1050, which doesn’t sound bad to the customer, but if they knew that when the prices were broken down, they were paying $50 for their breakfasts every morning, they might reconsider the price or demand a lower one, as they don’t eat breakfast anyway.

Tjan does point out that this is not always true. Fast food restaurants have the bundled (the value meals) and the individual item’s price points both visible on their menu boards. Customers can quickly see that the bundle of sandwich, fries, and drink is several cents cheaper than buying them separately. In this case, the bundling (having given up its inherent transparency) now benefits the customers. The company, however, does benefit from the increased speed and efficiency of the value meals, as their employees can greatly generate the meals. For a company focused on speed, this might be an overall benefit greater than the loss of a few cents per meal. This also benefits their marketing plans – by being able to advertise a lower price point, they could gain customers who are focused solely on price.

It should be noted, however, that customers are also less likely to purchase the whole package when not given a bundled option. If there were no value meals, many customers wouldn’t get the fries or drinks. They might just order a smaller meal. Or in terms of a car sales, the customer would be likely to not buy additional add-ons if they are all presented individually – customers are much more likely to either go all-in (all the add-ons available) or none (the bare minimum they can live with).

In these cases, therefore, buyers and sellers can both benefit from bundling. The lack of transparency in bundling does benefit the seller, especially when the seller wants to put a high price point on items that some customers would balk at paying. But the customer can also benefit when the seller’s objective in bundling isn’t the price, but the act of creating a better advertising market or a swifter, more efficient product.

In the end, bundling can also be seen as pricing based on value. The customers will pay the higher bundled price, if the extra add-ons were somewhat worth it (the fries) and doesn’t add that much to the price. The seller then benefits by the customers paying the higher, bundled prices for products they might not have purchased in the first place. This added value could possibly be seen as beneficial to both.

![[Slashdot]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/slashdot.png)

![[Digg]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/digg.png)

![[Reddit]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/reddit.png)

![[del.icio.us]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/delicious.png)

![[Facebook]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/facebook.png)

![[Technorati]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/technorati.png)

![[Google]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/google.png)

![[StumbleUpon]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/stumbleupon.png)

Posted in Pricing

Tags: Add-On, Anthony Tjan, Bundling, Cruise Package, Customer Retention, Fast Food Restaurants, Harvard Business Review, HBR, Price, Price Point, Pricing, Pricing Strategy, Value Pricing, Value Selling

March 17th, 2010 by

March 17th, 2010 by  Joern Meissner

Joern Meissner

Customers have a habit of demanding lower prices, especially when they believe a product’s price represents a huge profit for the company. The case in point here is e-books, just one of many digital products facing the e-pricing dilemma.

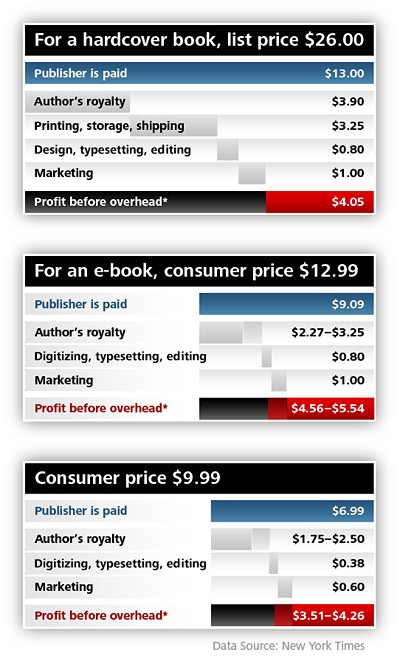

In recent weeks, thanks to the soon-to-be-released Apple iPad, five of the six major publishers banded together to demand a change in price. Up until now, Amazon, the leading e-book seller, has set most bestsellers at a $9.99 price point, but by making a deal with Apple to price books from $12.99 to $14.99 and threatening to remove their products from Amazon’s online store and it’s e-reader Kindle, the publishers were able to push up the price.

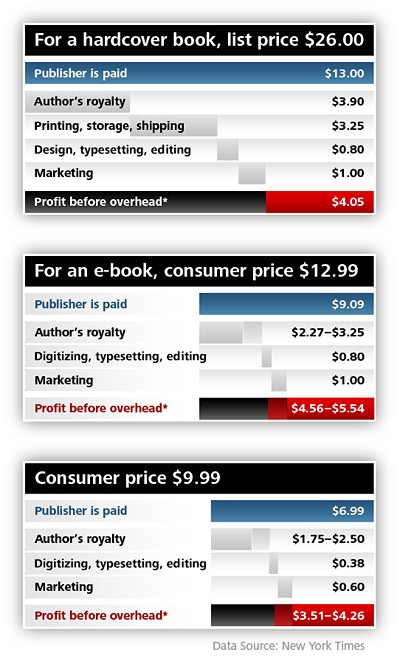

To illustrate why publishers keep pushing for the higher price, the recent New York Times article ‘Math of Publishing Meets the E-Book’ by Motoko Rich broke down standard hardcover book pricing and compared it to the new iPad digital pricing, also suggesting, according to Rich, that “customers have exaggerated the savings and have developed unrealistic expectations of how low the prices of e-books can go.”

A hardcover books costs about $26. After all the production, editing, marketing, and author’s royalties are paid (see graph), the publisher actually only sees about $4.05 in return, but that’s before any of the overhead bills are paid. Compare this to $12.99 digital price. In the new set-up with Apple, the publishers make between $4.56 to $5.54 in profit (see graph).

But this profit does not actually represent how much profit a publisher makes off any book. Like movie producers, publishers expect a loss on most of their products. Most books are published and disappear from the bookstore shelves long before the publisher recoups the author’s original advance and the original run’s printing costs. In the end, publishers truly only make money off major blockbuster books, further creeping into the publisher’s profitability.

On the other side of the pricing debate is the booksellers themselves. America only has two major booksellers left: Barnes N Noble and Borders, and many of the smaller independent have started shutting down due to Amazon. If the digital revolution takes hold with book-buying customers at too low a price point, it could also mean the end for traditional printed books, as there won’t be any bookstores left o sell them. Borders has already closed the majority of their stores in the U.K.

Some are advocating that the publishing world should step away from digital publishing and should discourage their customers from buying e-books by setting a high price for them. A similar idea has been put forth to save newspapers, which seems to be failing.

Many, however, realize that trying to hold back the digital revolution simply won’t work. Anne Rice, one of the most popular paranormal and horror writers in the world, said, “The only thing I know is a mistake is people trying to hold back e-books or Kindle and trying to head off the revolution by building a dam. It’s not going to work.” Publishers, a notoriously conservative business as a whole, are going to have to find a way to start looking towards the future, if they want to make their products viable and profitable once more.

![[Slashdot]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/slashdot.png)

![[Digg]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/digg.png)

![[Reddit]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/reddit.png)

![[del.icio.us]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/delicious.png)

![[Facebook]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/facebook.png)

![[Technorati]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/technorati.png)

![[Google]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/google.png)

![[StumbleUpon]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/stumbleupon.png)

Posted in Pricing

Tags: Amazon, Apple, Apple iPad, Barnes and Noble, Books, Borders, Demand, E-Book Pricing, E-Book Publishing, E-Books, E-Publishing, E-Readers, Elasticity, iPad, iTunes, Kindle, Macmillan, Motoko Rich, New York Times, NYT, Paying for Content, Price, Pricing, Publishing, Sony, United States, USA

March 2nd, 2010 by

March 2nd, 2010 by  Joern Meissner

Joern Meissner

There are three basic pricing strategies: skimming, neutral, and penetration. These pricing strategies represent the three ways in which a pricing manager or executive could look at pricing. Knowing these strategies and teaching them to your sales staff, and letting them know which one they should be using, allows for a unity within the company and a defined, company-wide pricing policy.

- Skimming Strategy

Skimming is the process of setting high prices based on value. Instead of basing your prices on your competition, a skimming price comes from within the company and the (financial) value your product represents to your customer. This strategy can be employed in emerging markets, where certain customers will always want the newest, most advanced product available. It also works well in a mature market, where customers have already realized the value of your product and are willing to pay for what they see as a worthwhile investment. Surprisingly, skimming also works in declining markets, as your diehard customers are willing to pay big bucks for what they see as an older but superior product with a dwindling supply.

- Neutral Strategy

In a neutral strategy, the prices are set by the general market, with your prices just at your competitors’ prices. The major benefit of a neutral pricing strategy is that it works in all four periods in the lifecycle. The major drawback is that your company is not maximizing its profits by basing price only on the market. Since the strategy is based on the market and not on your product, your company, or the value of either, you’re also not going to gain market share. Essentially, neutral pricing is the safe way to the play the pricing game.

- Penetration Strategy

A penetration strategy is the price war; this strategy goes for the deepest price cuts, driving at every moment to have your price be the lowest on the market. Penetration strategies only work in one of the four lifecycle periods: growth. During growth, your sales are continuing to expand, as your customers want the newest product but still a product that has already tested by others in the emerging period. This is when your average customer buys a product and when the sales numbers will be the biggest. A penetration strategy works here, and only here, because you’re attracting customers to a new but proven product with cheap productions. You’re developing relationships with new customers willing to try the new product but who will only come for a lower price.

Penetration strategies fail in the other lifecycle periods by leaving possible profits in the hands of the customers. In an emerging market, your product is brand new and customers who want it first should (and will) pay for that right. In a mature market, a price war will simply start the process of endless and useless competition, destroying your profit margin. In a declining market, only those who still must have your product will purchase it, and just like in an emerging period, they should (and will) pay for that right.

Knowing which pricing strategy works best for your company is an essential tool for any pricing manager and can only be found by recognizing the lifecycle of your products. If your entire sales force is on the same page in recognizing product lifecycles and utilizing pricing strategies, your company will likely see greater returns.

![[Slashdot]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/slashdot.png)

![[Digg]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/digg.png)

![[Reddit]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/reddit.png)

![[del.icio.us]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/delicious.png)

![[Facebook]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/facebook.png)

![[Technorati]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/technorati.png)

![[Google]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/google.png)

![[StumbleUpon]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/stumbleupon.png)

Posted in Pricing

Tags: Competition, Customer Retention, Lifecycle, Neutral Pricing, Neutral Pricing Strategy, Penetration, Penetration Pricing, Penetration Pricing Strategy, Penetration Strategy, Pricing, Pricing Strategy, Product Lifecycle, Skimming, Skimming Pricing, Skimming Pricing Strategy, Skimming Strategy, Strategy, Success

![]() May 20th, 2010 by

May 20th, 2010 by  Joern Meissner

Joern Meissner