March 23rd, 2010 by

March 23rd, 2010 by  Joern Meissner

Joern Meissner

Bundling is the act of grouping services and products together to create a new price point. This technique is common in most industries, but the question remains of whether the buyer or the seller actually benefits more from the bundling itself.

In the recent article ‘The Pros and Cons of Bundling’ by Anthony Tjan (The Harvard Business Review, February 26, 2010), Tjan discussed how bundling, in his opinion, ultimately benefits the seller. His argument is based on the lack of transparency in bundling; the sellers can group products and services together in a way that hides how much the customer pays for each individual item. This illusion then prompts the customer to pay more for simple items than they would if the bundle had been broken into a product-by-product invoice.

An illustration of this idea is when customers buy all-inclusion cruise packages – the customer does not know how much they are paying for each individual part of the cruise but only the total price. For example, the overall price for one person could $1050, which doesn’t sound bad to the customer, but if they knew that when the prices were broken down, they were paying $50 for their breakfasts every morning, they might reconsider the price or demand a lower one, as they don’t eat breakfast anyway.

Tjan does point out that this is not always true. Fast food restaurants have the bundled (the value meals) and the individual item’s price points both visible on their menu boards. Customers can quickly see that the bundle of sandwich, fries, and drink is several cents cheaper than buying them separately. In this case, the bundling (having given up its inherent transparency) now benefits the customers. The company, however, does benefit from the increased speed and efficiency of the value meals, as their employees can greatly generate the meals. For a company focused on speed, this might be an overall benefit greater than the loss of a few cents per meal. This also benefits their marketing plans – by being able to advertise a lower price point, they could gain customers who are focused solely on price.

It should be noted, however, that customers are also less likely to purchase the whole package when not given a bundled option. If there were no value meals, many customers wouldn’t get the fries or drinks. They might just order a smaller meal. Or in terms of a car sales, the customer would be likely to not buy additional add-ons if they are all presented individually – customers are much more likely to either go all-in (all the add-ons available) or none (the bare minimum they can live with).

In these cases, therefore, buyers and sellers can both benefit from bundling. The lack of transparency in bundling does benefit the seller, especially when the seller wants to put a high price point on items that some customers would balk at paying. But the customer can also benefit when the seller’s objective in bundling isn’t the price, but the act of creating a better advertising market or a swifter, more efficient product.

In the end, bundling can also be seen as pricing based on value. The customers will pay the higher bundled price, if the extra add-ons were somewhat worth it (the fries) and doesn’t add that much to the price. The seller then benefits by the customers paying the higher, bundled prices for products they might not have purchased in the first place. This added value could possibly be seen as beneficial to both.

![[Slashdot]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/slashdot.png)

![[Digg]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/digg.png)

![[Reddit]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/reddit.png)

![[del.icio.us]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/delicious.png)

![[Facebook]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/facebook.png)

![[Technorati]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/technorati.png)

![[Google]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/google.png)

![[StumbleUpon]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/stumbleupon.png)

Posted in Pricing

Tags: Add-On, Anthony Tjan, Bundling, Cruise Package, Customer Retention, Fast Food Restaurants, Harvard Business Review, HBR, Price, Price Point, Pricing, Pricing Strategy, Value Pricing, Value Selling

March 17th, 2010 by

March 17th, 2010 by  Joern Meissner

Joern Meissner

Customers have a habit of demanding lower prices, especially when they believe a product’s price represents a huge profit for the company. The case in point here is e-books, just one of many digital products facing the e-pricing dilemma.

In recent weeks, thanks to the soon-to-be-released Apple iPad, five of the six major publishers banded together to demand a change in price. Up until now, Amazon, the leading e-book seller, has set most bestsellers at a $9.99 price point, but by making a deal with Apple to price books from $12.99 to $14.99 and threatening to remove their products from Amazon’s online store and it’s e-reader Kindle, the publishers were able to push up the price.

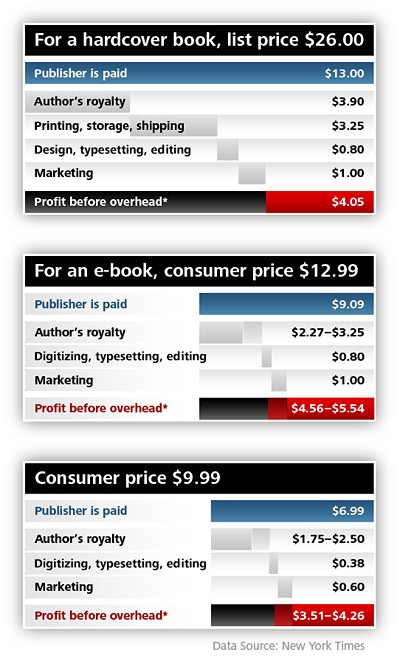

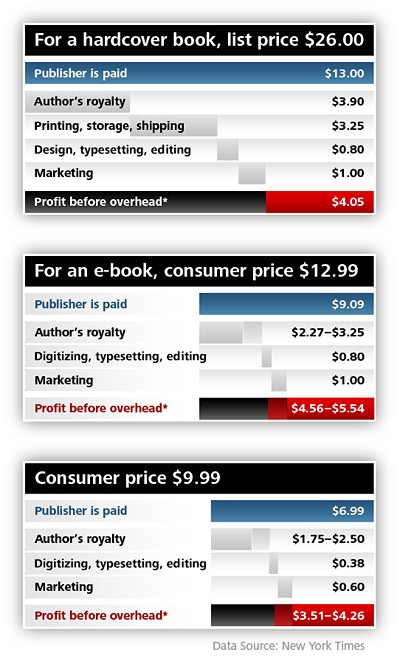

To illustrate why publishers keep pushing for the higher price, the recent New York Times article ‘Math of Publishing Meets the E-Book’ by Motoko Rich broke down standard hardcover book pricing and compared it to the new iPad digital pricing, also suggesting, according to Rich, that “customers have exaggerated the savings and have developed unrealistic expectations of how low the prices of e-books can go.”

A hardcover books costs about $26. After all the production, editing, marketing, and author’s royalties are paid (see graph), the publisher actually only sees about $4.05 in return, but that’s before any of the overhead bills are paid. Compare this to $12.99 digital price. In the new set-up with Apple, the publishers make between $4.56 to $5.54 in profit (see graph).

But this profit does not actually represent how much profit a publisher makes off any book. Like movie producers, publishers expect a loss on most of their products. Most books are published and disappear from the bookstore shelves long before the publisher recoups the author’s original advance and the original run’s printing costs. In the end, publishers truly only make money off major blockbuster books, further creeping into the publisher’s profitability.

On the other side of the pricing debate is the booksellers themselves. America only has two major booksellers left: Barnes N Noble and Borders, and many of the smaller independent have started shutting down due to Amazon. If the digital revolution takes hold with book-buying customers at too low a price point, it could also mean the end for traditional printed books, as there won’t be any bookstores left o sell them. Borders has already closed the majority of their stores in the U.K.

Some are advocating that the publishing world should step away from digital publishing and should discourage their customers from buying e-books by setting a high price for them. A similar idea has been put forth to save newspapers, which seems to be failing.

Many, however, realize that trying to hold back the digital revolution simply won’t work. Anne Rice, one of the most popular paranormal and horror writers in the world, said, “The only thing I know is a mistake is people trying to hold back e-books or Kindle and trying to head off the revolution by building a dam. It’s not going to work.” Publishers, a notoriously conservative business as a whole, are going to have to find a way to start looking towards the future, if they want to make their products viable and profitable once more.

![[Slashdot]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/slashdot.png)

![[Digg]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/digg.png)

![[Reddit]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/reddit.png)

![[del.icio.us]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/delicious.png)

![[Facebook]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/facebook.png)

![[Technorati]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/technorati.png)

![[Google]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/google.png)

![[StumbleUpon]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/stumbleupon.png)

Posted in Pricing

Tags: Amazon, Apple, Apple iPad, Barnes and Noble, Books, Borders, Demand, E-Book Pricing, E-Book Publishing, E-Books, E-Publishing, E-Readers, Elasticity, iPad, iTunes, Kindle, Macmillan, Motoko Rich, New York Times, NYT, Paying for Content, Price, Pricing, Publishing, Sony, United States, USA

March 10th, 2010 by

March 10th, 2010 by  Joern Meissner

Joern Meissner

With a vision to create a four-year doctoral program in statistics and operations that was based in practical knowledge and real-world implementations for managerial science, Lancaster University has opened its newest Doctoral Training Centre in Statistic and Operations. Named STOR-i, for “Statistics and Operational Research – excellence with impact”, the new 4 year program is focused on creating a new generation of advanced problem-solvers with high technical knowledge and the ability to create significant methodological contributions to STOR.

The program’s history started in December 2009 when the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) announced a new investment of 13 million pounds to create Doctoral Training Centres at Lancaster, Cambridge, and Warwick universities. Lancaster’s program, with the combined 6.7 million pound award shared jointly between the Departments of Mathematics and of Statistics and Management Science, will build on its leading reputation in these fields. Recent accomplishments in these programs have included the success of the EPSRC Science and Innovation award in Operational Research (the LANCS Initiative) and the HEFCE-funded Centre for Excellence in Teach and Learning in Postgraduate Statistics. STOR-i will quickly add its real-world focus to the programs’ accomplishments.

STOR-i has partnered with industrial multinational companies, like Unilever Research and Shell Research, who will be directly involved with the students’ training. They will provide real-world experience throughout the program. After the student completes the first year coursework to provide a practical grounding in STOR’s mathematical core and an overview of current methodology, the student will work towards the PhD under the guidance of supervisory teams. Half of these projects will include actual industrial involvement and the added guidance of an industrial collaborator.

The Centre, led by Chairman Kevin Glazebook, Director Jonathan Tawn, and Deputy Director Idris Eckley, will train at least 40 students over seven years, and will begin to admit the first of these students in October 2010. More information about the program and how to apply can be found at www.stor-i.lancs.ac.uk.

![[Slashdot]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/slashdot.png)

![[Digg]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/digg.png)

![[Reddit]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/reddit.png)

![[del.icio.us]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/delicious.png)

![[Facebook]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/facebook.png)

![[Technorati]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/technorati.png)

![[Google]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/google.png)

![[StumbleUpon]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/stumbleupon.png)

Posted in Lancaster University

Tags: Aviation, Banking, Cambridge, DCT, Doctoral Training Centre, Energy, EPSRC, EPSRC Science and Innovation Award, HEFCE, Higher Education Funding Council for England, Idris Eckley, Jonathan Tawn, Kevin Glazebrook, Lancaster University, Lancaster University Management School, LANCS Initiative, LUMS, Management Science, Operational Research, Operations Research, Shell, Shell Research, Statistics, STOR-i, Unilever, Unilever Research, Warwick

March 4th, 2010 by

March 4th, 2010 by  Joern Meissner

Joern Meissner

The story of the digital price wars is all about change. As each new technology develops and transitions into part of the mainstream culture, the way the average customer buys their goods is dramatically altered. And the price that customers pay must change right along with it.

According to the recent article ‘Is the price right for e-books?’ by BBC blogger Rory Cellan-Jones, the war over the price for e-book content is poised to become a major issue for the publishing world over the next year in the United Kingdom.

With Amazon, Sony, and Barnes N Noble all developing their own portable reading devices, UK patrons still complain that high prices and lousy access to the books they want have stopped them from purchasing e-books. This has allowed smaller companies like Kobobooks to develop e-readers that allow for easy reading across platforms (portable device, TV, computer, etc.) and easier, faster downloads.

However, it appears most customers care more about the price of the book then how they get it or where they can read it. With Amazon in a power struggle with publishers both in the UK and in America over who determines the price of books, the standard pricing for any book is far from being decided. In fact, just last month Macmillan, one of “Big Six” English language publishers, blocked Amazon from selling any of their products, in a move designated to keep digital book prices high. Macmillan and Amazon may have compromised, but this was surely just one skirmish in a long war.

Perhaps Amazon should focus on how Apple transformed the music world with iTunes. By designating a simple pricing scheme (99 cents per song), Apple was able to give customers the access, speed, and (most importantly) price they wanted. They also won many court cases that gave them the right to determine their own prices. If Amazon and the other e-readers can follow suit, a bottom line price could help drive e-books and e-readers into the hands of every UK citizen.

![[Slashdot]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/slashdot.png)

![[Digg]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/digg.png)

![[Reddit]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/reddit.png)

![[del.icio.us]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/delicious.png)

![[Facebook]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/facebook.png)

![[Technorati]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/technorati.png)

![[Google]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/google.png)

![[StumbleUpon]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/stumbleupon.png)

Posted in Pricing

Tags: Amazon, Apple, Barnes and Noble, Books, E-Books, E-Publishing, E-Readers, iTunes, Kindle, Macmillan, Paying for Content, Price, Publishing, Rory Cellan-Jones, Sony, UK, United Kingdom

March 2nd, 2010 by

March 2nd, 2010 by  Joern Meissner

Joern Meissner

There are three basic pricing strategies: skimming, neutral, and penetration. These pricing strategies represent the three ways in which a pricing manager or executive could look at pricing. Knowing these strategies and teaching them to your sales staff, and letting them know which one they should be using, allows for a unity within the company and a defined, company-wide pricing policy.

- Skimming Strategy

Skimming is the process of setting high prices based on value. Instead of basing your prices on your competition, a skimming price comes from within the company and the (financial) value your product represents to your customer. This strategy can be employed in emerging markets, where certain customers will always want the newest, most advanced product available. It also works well in a mature market, where customers have already realized the value of your product and are willing to pay for what they see as a worthwhile investment. Surprisingly, skimming also works in declining markets, as your diehard customers are willing to pay big bucks for what they see as an older but superior product with a dwindling supply.

- Neutral Strategy

In a neutral strategy, the prices are set by the general market, with your prices just at your competitors’ prices. The major benefit of a neutral pricing strategy is that it works in all four periods in the lifecycle. The major drawback is that your company is not maximizing its profits by basing price only on the market. Since the strategy is based on the market and not on your product, your company, or the value of either, you’re also not going to gain market share. Essentially, neutral pricing is the safe way to the play the pricing game.

- Penetration Strategy

A penetration strategy is the price war; this strategy goes for the deepest price cuts, driving at every moment to have your price be the lowest on the market. Penetration strategies only work in one of the four lifecycle periods: growth. During growth, your sales are continuing to expand, as your customers want the newest product but still a product that has already tested by others in the emerging period. This is when your average customer buys a product and when the sales numbers will be the biggest. A penetration strategy works here, and only here, because you’re attracting customers to a new but proven product with cheap productions. You’re developing relationships with new customers willing to try the new product but who will only come for a lower price.

Penetration strategies fail in the other lifecycle periods by leaving possible profits in the hands of the customers. In an emerging market, your product is brand new and customers who want it first should (and will) pay for that right. In a mature market, a price war will simply start the process of endless and useless competition, destroying your profit margin. In a declining market, only those who still must have your product will purchase it, and just like in an emerging period, they should (and will) pay for that right.

Knowing which pricing strategy works best for your company is an essential tool for any pricing manager and can only be found by recognizing the lifecycle of your products. If your entire sales force is on the same page in recognizing product lifecycles and utilizing pricing strategies, your company will likely see greater returns.

![[Slashdot]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/slashdot.png)

![[Digg]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/digg.png)

![[Reddit]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/reddit.png)

![[del.icio.us]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/delicious.png)

![[Facebook]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/facebook.png)

![[Technorati]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/technorati.png)

![[Google]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/google.png)

![[StumbleUpon]](http://www.meiss.com/blog/wp-content/plugins/slashdigglicious/icons/stumbleupon.png)

Posted in Pricing

Tags: Competition, Customer Retention, Lifecycle, Neutral Pricing, Neutral Pricing Strategy, Penetration, Penetration Pricing, Penetration Pricing Strategy, Penetration Strategy, Pricing, Pricing Strategy, Product Lifecycle, Skimming, Skimming Pricing, Skimming Pricing Strategy, Skimming Strategy, Strategy, Success

![]() March 23rd, 2010 by

March 23rd, 2010 by  Joern Meissner

Joern Meissner